Water Stewardship Committee

The purpose of the Colorado Water Stewardship Project (CWSP) is to ensure that the Colorado Water Congress members and water stakeholders from around the state are prepared for ballot initiatives of interest to Colorado's water community.

Specifically, the project analyzes public understanding of the Doctrine and informs water stakeholders of the implications of a Public Trust Doctrine in Colorado. CWSP monitors all ballot filings and legal actions for a Public Trust Doctrine and challenges these to every possible extent.

Rights of Nature Information

Information can be found HERE (pdf).

Proposed Ballot Initiatives

Hill v. Warsewa

The Colorado Water Stewardship Project has been monitoring the Hill v. Warsewa (Case No. 18-cv-01710-KMT). The case centers around Roger Hill, who filled a complaint on May 31, 2018 with the state district court in Fremont County. The complaint included a declaratory judgment claim, seeking determination that a portion of the Arkansas River was property of the State of Colorado, "to be held in trust for the public."

On June 6, 2023 the Colorado Supreme Court issued a unanimous opinion on the case: Justice Hart's short opinion simply corrects the error and inconsistency in the Court of Appeals' decision in 2022. If Hill cannot quiet title to establish State ownership of the riverbed across Warsewa's property, neither can he obtain a declaratory judgment that is premised on State ownership. The Court concluded that Hill has no "legally protected interest" - no substantive right to be redressed by the procedural mechanism of a declaratory judgment. The opinion quotes the assertions in Hill's complaint that the State owns the riverbed in "trust for the public," and explains that "proof of the State's ownership of the riverbed is a necessary prerequisite to his claimed right to fish" in the river crossing Warsewa's property.

The opinion does not address the public trust doctrine, except in the opening paragraph noting the issues extensively discussed in briefing that are "ultimately irrelevant" to the one question the Court decided. However, Hill argued the public trust doctrine gave him a "legally protected interest" in showing State ownership, and the Court did not buy that argument for an end-run around his inability to quiet title for the State.

The end result of this decision is the complete dismissal of Hill's lawsuit. While it's possible Hill may try to file another suit on a narrower theory that doesn't depend on State ownership or a public trust, the decision should put an end to private claims of navigability as a means to litigate the public trust doctrine in Colorado. Only the State of Colorado can bring claims of ownership based on navigability at statehood; others cannot force such claims upon the State. - Steve Leonhardt, Burns, Figa & Will P.C.

- COLORADO SUPREME COURT OPINION (06-05-2023)

- READ THE SUMMARY OF THE 2019 DECISION

- READ THE ORDER DISMISSING THE CASE

- DOCKETING STATEMENT

- CWC AMICUS BRIEF (01-21-2021)

- CWC THANK YOU

Public Trust Doctrine

The Public Trust Doctrine is the concept that Colorado’s environment is the common property of all Coloradans. Governments are to act as trustees of air, water, natural, and scenic values for the benefit of all the people.

The Doctrine would:

- Impose governmental control upon Colorado’s water rights system.

- Subordinate all water rights to a new, undefined public use without just compensation.

- Undermine municipal, recreational, environmental, and agricultural water supplies.

- Require enormous costs to replace lost water rights.

- Raise questions of state liability for taking vested property rights.

The Public Trust Doctrine holds no legal authority in Colorado, and is inconsistent with (i) the Colorado Constitution, (ii) existing state laws, and (iii) over 150 years of Colorado case law and water allocation. The Colorado Water Congress opposes public trust initiatives on the grounds they are unwise, unnecessary, expensive and disruptive to the fair and responsible allocation and stewardship of Colorado’s water resources.

Colorado Water Stewardship Project Charter

The CWSP is a Colorado Water Congress (CWC) special project separately funded and managed by CWC members who are deeply concerned about the impact of any Public Trust Doctrine development that would undermine Colorado’s Prior Appropriation Doctrine.

Mission Statement:

To ensure that CWC members and water stakeholders from around the state are prepared for any Public Trust Doctrine initiative that would disrupt ownership or management of Colorado’s water resources, by assessing ballot filings, judicial, regulatory, and legislative actions related to a Public Trust Doctrine, assessing the public level of knowledge and support for the doctrine, and implementing a communication and action plan to protect Colorado’s water community from adverse impacts.

Membership:

Members shall be persons who have an interest in the protection of the Prior Appropriation System.

Active membership of the CWSP shall consist of representatives of organizations (or individuals) that are active members of the CWC and have provided funding for the CWSP within the previous 36 months. If a tallied vote is necessary for any reason, then only those active members present at the meeting may contribute.

Officers:

Officers will consist of a Chair and a Vice-Chair. Each officer shall be elected at-large by a vote of the active members. Both positions are a two-year commitment. In the event that either position is vacated, then the remaining position shall take on the responsibility of both Chair and Vice-Chair until a suitable replacement is found or until one is elected. There is no limit to the number of consecutive terms that an officer may hold a position. Responsibilities of each officer are listed below in the “Biennial Cycle” section.

Meetings:

The CWSP shall meet quarterly, at a minimum. It is anticipated that the meetings will occur on the second Monday of March, June, September, and December. Additional meetings may be held, with an advanced notice to the membership, to work through critical matters.

Funding:

The CWSP operates in line with the Water Year (October 1st to September 30th) and meets quarterly. In the September quarterly meeting, members will agree on a proposed budget for the subsequent year. Once a budget has been agreed upon, with input provided by project leadership and CWC staff, “General Funding” letters will be sent out to prior and current CWSP funders. Because of the unpredictable nature of proposed initiatives and litigation threatening the legal foundation for water

rights in Colorado, the CWSP aims to maintain a minimum $50,000 reserve balance in addition to funds for the planned and approved operating budget.

Should the CWSP ever be dissolved, all previously approved debts will be paid and the remaining funding balance will be returned to the active members minus a 5% administrative charge to be kept by CWC. The amount refunded will be prorated to the amount provided by each active member during the previous 36 months from the dissolution date.

Biennial Cycle:

The CWSP will operate on a two-year planning cycle.

At a time near the December meeting for odd number years, the CWSP will host a webinar – open to all – to highlight the importance of tracking ballot initiatives. As topics of emerging threat to the Prior Appropriation System arise, the CWSP may host additional webinars open to general attendance.

Reoccurring tasks and responsible parties are detailed in the table below

| Year | Month | Task | Responsible Party |

| Odd | March | Strategic Outline Update | Chair |

| Odd | June | Summary Update | Vice Chair |

| Odd | September | Budget | CWSP Committee |

| As Needed | Webinar on Ballot Initiatives and Other Issues as Needed | Chair | |

| Even | March | Strategic Outline Update | Chair |

| Even | June | Background &History Update | Vice Chair |

| Even | September | Budget | CWSP Committee |

| Even | December | Officer Selection | CWSP Committee |

Since 1994, the Colorado Water Congress (CWC) has engaged in several legal proceedings to preserve Colorado’s constitutionally established prior appropriation system against threatened legal changes, particularly from proposed constitutional amendments. It has done so through the Colorado Water Stewardship Project (Project). The Project has studied public understanding of the Public Trust Doctrine and informs water stakeholders of the implications of a Public Trust Doctrine in Colorado. Despite many attempts to enact various forms of the Public Trust Doctrine in Colorado, the CWC and its allies have successfully defended the Colorado Constitution and preserving the Colorado water rights system, having devoted significant resources toward doing so.

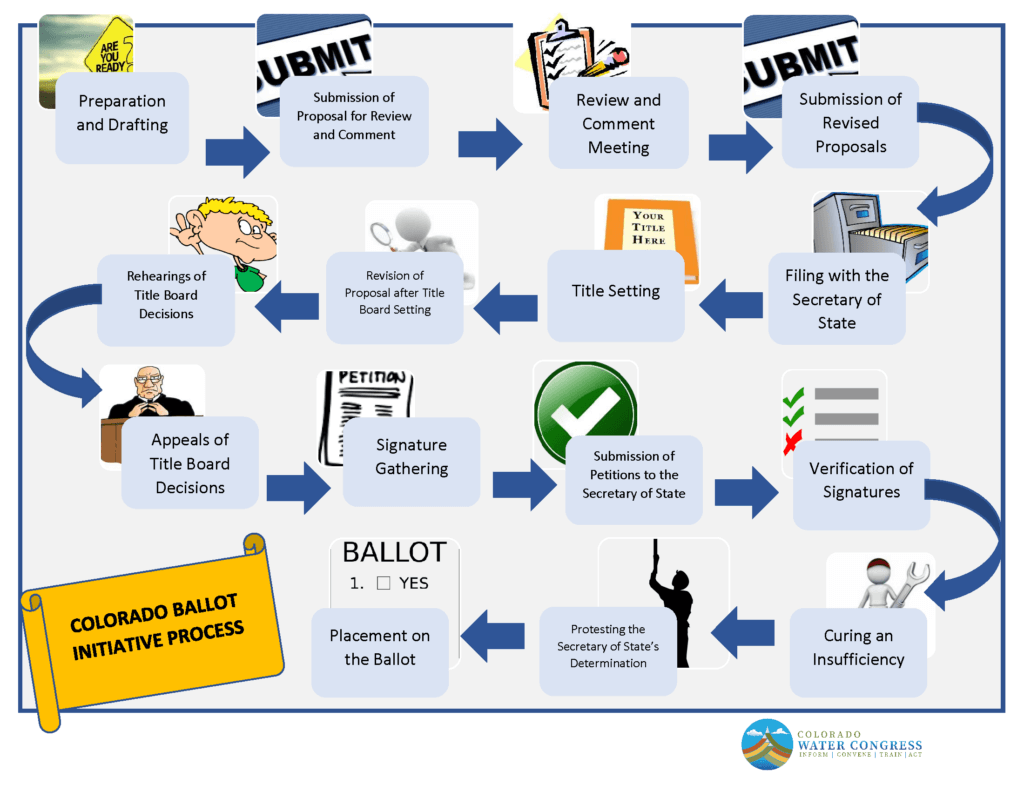

The Project also ensures that CWC members and water stakeholders from around the state are prepared for ballot initiatives of interest to Colorado’s water community. In short, the Project monitors all ballot measures and legal actions toward a Public Trust Doctrine and challenges these to every possible extent. Due to the nature of Colorado’s ballot initiative petition process and limited opportunities to challenge proposed initiatives, the Project has often engaged in the ballot title setting process, with immediate appeals to the Colorado Supreme Court when necessary.

Summary of Significant Initiatives and Cases Since 1994 i. 1994 Public Rights Initiative

The 1994 Public Rights Initiative had multiple features. First, it required Colorado “adopt and defend a strong public trust doctrine regarding the public’s rights and ownerships in and of the waters in Colorado.” Though this “strong public trust doctrine” was not defined in the measure, the lead proponent, Richard Hamilton, suggested the phrase would go at least as far as California’s public trust doctrine, which imposed a public trust on most surface and tributary waters in the state.

The second clause of the 1994 Initiative would require the State to “protect and defend the public’s interests in waters from unwarranted or otherwise narrow definitions of its waters as private property.” This clause “insist[ed] that public waters never be defined as private property.”

The final section provided for public ownership of waters dedicated to instream or in-lake uses through the Colorado Water Conservation Board (CWCB). The CWCB would be required to accept, protect, and defend ownership rights in the use of waters which were decreed to public use.

The 1994 Initiative also contained provisions that would substantially alter the law governing water conservancy districts, imposing new requirements for elections on those districts’ board members and boundary changes.

The Ballot Title Setting Board (Title Board) set a title for the initiative. CWC appealed, arguing the ballot title language was unclear and improper, but the Colorado Supreme Court affirmed the Title Board’s decision. Despite the proponents’ signature collection efforts, the initiative did not appear on the ballot.

ii. 1995 Public Rights Initiative

Colorado voters adopted a new constitutional amendment in November 1994, requiring that all ballot initiatives contain only one subject. The single subject requirement is designed to “prevent surprise and fraud from being practiced upon the voters.” Since 1995, CWC has challenged several proposed ballot initiatives based on single-subject requirement.

The 1995 Public Rights Initiative (1995 Initiative) was nearly identical to the 1994 initiative.

After the Title Board set titles for the 1995 Initiative, CWC appealed the Title Board’s decision to the Colorado Supreme Court. Because two paragraphs of the Initiative discussed water district election requirements and two addressed public trust water rights, the Colorado Supreme Court determined the initiative unconstitutionally addressed multiple subjects, reserved the Title Board’s decision, directing the Title board to strike the 1995 Initiative, and return the initiative to its proponents.

This decision was the Colorado Supreme Court’s first case on the new single subject requirement, and it prevented the 1995 Initiative from any further progress toward the ballot.

iii. 2007 Ballot Initiative 17

Initiative 17 in 2007 proposed a constitutional amendment to create a new state “Department of Environmental Conservation.” The initiative gave this department “trust responsibilities” to favor “public ownerships and public values” over competing economic interests.

Following title setting on this amendment, CWC appealed to the Colorado Supreme Court. In a 4-3 decision, the Court reversed the Title Board and invalidated Initiative 17. Justice Gregory Hobbs’ majority opinion explains the “mandatory public trust standard for agency decision-making” was “a variation on” the “public trust doctrine... coiled in the folds of the measure.” Accordingly, the Colorado Supreme Court ruled in favor of the CWC and prevented Initiative 17 from reaching the ballot.

iv. 2012 Ballot Initiative 3

Initiative 3 proposed to amend section 5 of Article XVI of the Colorado Constitution (part of the foundation for the prior appropriation system) by adding provisions to adopt and define a “Colorado public trust doctrine.” This doctrine would protect public ownership rights and interests in the water of natural streams while giving “the public’s estate in water in Colorado...legal authority superior to rules and terms of contracts or property law.” Initiative 3 also expressly provided for “access by thepublic along, and on, the wetted natural perimeter of a stream bank of a water course of any natural stream in Colorado” as a “navigation servitude for commerce and public use as recognized in the Colorado public trust doctrine.”

CWC appealed this Initiative from the Title Board to the Colorado Supreme Court, arguing that Initiative 3 impermissibly combined two subjects: 1) the adoption of a “public trust doctrine” and 2) the transfer of real property from private landowners to the public.

The Colorado Supreme Court affirmed the Title Board’s decision with Justice Hobbs dissenting. Justice Hobbs opined that, though a casual reading of the Initiative could lead a voter to believe he is a reaffirming Colorado’s long standing water law doctrine, there are three subject matters that “propose to drop what amounts to a nuclear bomb on Colorado water rights and land rights.”

The proponents of the Initiative failed to gather enough signatures, so Initiative 3 never made the ballot.

v. 2012 Ballot Initiative 45

In 2012, the same proponents (Richard Hamilton and Philip Doe) also proposed Initiative 45, seeking to amend section 6 of Article XVI of the Colorado Constitution by broadening constitutional diversion rights, then limiting such diversions to protect the public’s estate.

First, the amendment would delete words that limit the diversion right to “unappropriated” waters of “natural stream[s],” thus extending that right to “any water within the state of Colorado.” The amendment would then add several provisions to limit appropriation rights, somewhat like the terms in Initiative 3, but without mentioning “public trust doctrine.” Initiative 45 provided for diversions to be limited or curtailed to “protect natural elements of the public’s dominant water estate” and required “ the water use appropriator to return water unimpaired to the public...”

CWC appealed the Title Board’s decision to set the title to the Colorado Supreme Court, arguing that the initiative violated the single subject requirement by combining 1) subordination of water diversion and use rights to a dominant public water estate, 2) expanding the scope of water appropriation under the state constitution, and 3) imposing a requirement that appropriators return water to the stream.

As with Initiative 3, the Title Board’s decision was affirmed with Justice Hobbs dissenting. Justice Hobbs agreed with CWC, stating that “three subjects are concealed within the folds of this complex initiative. Any one of these subjects might lead a voter to vote for the initiative even though the voter does not favor one or more of the other subjects.” Justice Hobbs also warned the initiative would “subordinate all existing water rights in Colorado created over the past 150 years to a newly created ‘public’s dominant water estate’.” Again, like Initiative 3, the proponents failed to gather enough signatures and the initiative never made the ballot.

vi. 2014 Ballot Initiative 89

Initiative 89 sought to amend the Colorado Constitution by adding a new article creating a “public trust, environmental rights, and local control” over natural resources. The amendment declared that Colorado’s environment is “the common property of all Coloradoans”; conservation of Colorado’s environment is “fundamental;” Colorado’s environment should be “protected and preserved” for all Coloradans, including future generations; state and local governments are “trustees” over the environment; and, if locally enacted laws conflict with state-enacted laws, the “more restrictive and protective law or regulation shall govern.”

CWC appealed the Title Board’s decision setting the title to the Colorado Supreme Court, arguing that Initiative 89 violated the single subject rule since it created a common property right to the environment, adopted a form of public trust doctrine, and imposed local control over environmental regulations with the authority to supersede any less restrictive state environmental regulations.

The Court affirmed the Title Board’s decision – with Justice Hobbs again dissenting (joined by Chief Justice Nancy Rice). Their dissent opined that the initiative combined two separate subjects: it fundamentally changed Colorado property law by creating a “common property” in the environment, and it granted new powers to both home-rule and statutory municipalities. The dissenting Justices observed that the proposed amendment would be a “quantum leap from the common law public trust doctrine.”

Then-Congressman Jared Polis was a leading supporter of Initiative 89. After signatures were submitted to the Secretary of State for Initiative 89, but before the signatures were counted, Gov. John Hickenlooper negotiated a compromise with then-Congressman Polis whereby Colorado formed an Oil and Gas Task Force and Initiative 89 was withdrawn from the ballot.

vii. Amendment 71 (2016)

Colorado’s voters adopted Amendment 71 in 2016, strengthening the requirements for introducing and adopting future ballot measures to amend the Colorado Constitution. To introduce a constitutional amendment, proponents must now gather the signatures not only from 5% of the total number of votes cast for all candidates for Secretary of State in the previous general election (as previously required), but also from at least 2% of registered votes in each of Colorado’s 35 state senate districts. Once on the ballot, a constitutional amendment must be approved by at least 55% of the total votes cast on the issue. After voters passed Amendment 71, several proponents of other initiatives challenged it in federal court.

The U.S. District Court for the District of Colorado ruled that the new signature requirement in Amendment 71 violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment and, accordingly, struck down Amendment 71. The District Court found that Amendment 71 was unconstitutional because it afforded more voting power to voters in state senate districts with a smaller proportion of registered voters.

The Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the District Court’s order, with CWC filing a brief as amicus curiae in support of Amendment 71 in the appeal. CWC argued, and the Tenth Circuit agreed, that Amendment 71 did not violate the Equal Protection Clause because state senate districts were based on approximately equal population (a constitutional method of apportioning districts) and Amendment 71 permissibly uses these districts in its requirement for geographic distribution of signatures. The Tenth Circuit upheld Amendment 71, so its petition and supermajority requirements now apply to Colorado constitutional amendments.

viii. Hill v. Warsewa (2018-present)

This court case, now pending on appeal, involves an effort to impose a public trust doctrine by litigation in Colorado and stemmed from a dispute between a fly fisherman, Roger Hill, and landowners, Mark Warsewa and Linda Joseph, on the Arkansas River above the Royal Gorge. Mr. Hill contended he had a right to fish on a particular spot on the Arkansas River because the riverbed belonged to the state of Colorado; Mr. Warsewa and his wife believed they had the right to control access to their property including denying permission to people walking onto and on the riverbed. In 2019, Magistrate Judge Kathleen Tafoya of the U.S. District Court of Colorado ruled against Mr. Hill, concluding that he did not have “standing” to sue. Mr. Hill then took the case to the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals, where Judge Paul

Kelly held the district court erred in dismissing the case entirely. Judge Tafoya then held that there was no federal jurisdiction because Mr. Hill only claimed injury as part of the general public, and returned the case to state court.

Following another dismissal, the case made its way to the Colorado Court of Appeals in October 2020. The State and landowners filed answer briefs in January 2021. The CWC filed an amicus brief (joined by Colorado Springs Utilities and the Upper Arkansas Water Conservancy District), supporting the defense in the appeal and asking to affirm the dismissal of the case, explaining that Mr. Hill’s public trust theory is contrary to Colorado law.

Committee documents are available in your Member Info Hub under Resources. You can log into the Member Info Hub through Member Login from the menu on the top of the screen or HERE.